90 years exhibition: Understanding the link between terroir, landscape and product identity

The terroir combines the natural environment, human practices and collective know-how. Visible in the landscape, the combination of these criteria gives a PDO its typical character, protected by the INAO.

LA NOTION DE TERROIR, SOCLE HISTORIQUE DES AOP

Terroir is a delimited geographical area in which a human community has, over the course of its history, built up a collective knowledge of production, based on a system of interactions between a physical and biological environment, and a set of human factors. The technical itineraries thus brought into play reveal an originality, confer a typicality, and result in a reputation, for a good originating in this geographical area.

Terroir is a living concept, evolving and open to innovation, which protects local specificities. It includes:

- Physical environment: water, climate, soils, rocks... Biodiversity: biological richness of the territory (plant, animal species...)

- Knowledge: knowledge of the growing cycle, adaptation to natural conditions... Skills: livestock or crop management, pruning, maturing, manufacturing techniques...

- Collective history: building shared rules within a community

The PDO is a tool for recognizing the terroir. Thanks to demanding specifications, it provides a framework for practices and guarantees that all stages of production take place in the defined geographical area.

LE PAYSAGE, TÉMOIN VISIBLE DU TERROIR

Landscape is a part of a territory, as perceived by local inhabitants or visitors, that evolves over time under the effect of natural forces and human action

.

In Normandy's Pays d'Auge region, the terroir (mild climate, rich soils, grazing know-how) has shaped a landscape of meadow orchards where tall apple trees and meadows share the space.

Cows graze under the trees, tending the grass and fertilizing the soil, maintaining the bocage balance necessary for the production of cider apples for the manufacture of Calvados.

WHAT IS THE LINK BETWEEN TERROIR AND LANDSCAPE?

Landscape gives a glimpse of terroir: it is both its reflection and its result.

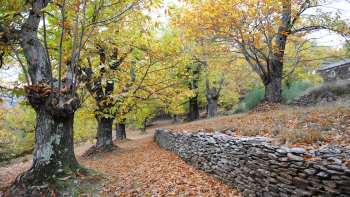

The physical environment (relief, climate, soils...) shapes the landscape: it conditions the location of crops, the shape of plots, the presence of hedges, low walls or terraces to adapt to the terrain.

Farming practices and know-how handed down from generation to generation also shape the landscape: extensive livestock farming, hillside vineyards or orchards organize characteristic landscapes.

Rural architecture (cellars, sheepfolds, drying sheds...) bears witness to these activities and punctuates the territory. The landscape thus tells the singular story of a community that lives and works in a given place.

Finally, the terroir is protected by PDOs, which set production rules and help maintain these landscapes: by imposing certain practices, they avoid standardization and preserve the balance between nature, culture and local identity.

.Cevennes terraces (faïsses, bancels), built of dry stone to gain ground on steep slopes, make it possible to create cultivable surfaces where the mountain left no space.

They bear witness to human adaptation to heavy Mediterranean rains by retaining soil, controlling water runoff, and thus participate in the formation of a unique terroir, essential to the cultivation of Cévennes sweet onions.

THE LINK BETWEEN LAND AND PRODUCT IDENTITY: PROOF FOR CHEESE APPELLATIONS VIA THE MÉTAPDOCHEESE PROGRAM

A research program, the fruit of a partnership between INRAe, the Conseil National des Appellations Laitières (CNAOL), the dairy interprofession (CNIEL) and FranceGénomique, has for 5 years analyzed the microbial flora of 440 milks and 1,300 cheeses, from 44 French cheese PDOs, using metagenomic methods.

Metagenomics is the method used to study microbiota, i.e. all micro-organisms (bacteria, viruses, fungi, yeasts) living in a specific environment. It is carried out by sequencing and analyzing the DNA contained in a medium.

The results precisely demonstrate the link between the terroir of each appellation and the nature of the microbial flora of each cheese. The project has thus made it possible to highlight the link between the specificities of a cheese's microbial ecosystem and everything that goes to make up the specificities of an AOP: a given area and specific practices at all levels of production. These results shed new light on the concept of "terroir".

In Haut-Léon, in northern Finistère, the terroir (mild oceanic climate, regular rainfall and silty soils) has favored the development of a vegetable-growing area facing the sea. The "Oignon de Roscoff" (Roscoff onion) grows on a plateau sloping towards the English Channel, cut by small rivers that join the coast. The marine climate limits temperature variations and protects the crop all year round. This open landscape, punctuated by fields of vegetables, bears the trace of a know-how linked to maritime trade: these onions, once shipped to Roscoff, were exported to Great Britain by the "Johnnies".

.In Camargue, the terroir combines vast wetlands, meadows and garrigues, making up a landscape of marshes, sansouïres and natural lawns.

Raising the Taureau de Camargue, run free and exclusively in the open air, helps preserve the wild character of the herd while maintaining ecological balance.

The bulls spend at least six months each year in the wetlands without being fed: by grazing and trampling, they control the growth of certain plants, maintain open environments and prevent habitats from closing.

This practice thus promotes a mosaic of varied vegetation and supports a specific biodiversity, closely linked to this Camargue landscape.

In the mountainous areas of southern France, fine lavender thrives on poor, dry and often rocky soils, where no other crop is viable.

Lands once cultivated and then abandoned are quickly colonized by hardy plants like lavender and aspic, which cover the hills and protect the soil from erosion. Lavender cultivation thus shapes an emblematic landscape of plateaus, slopes and hills covered with purple fields, a visible mark of the Mediterranean terroir and of the inhabitants' adaptation to these difficult lands.

In the Basque country, the mild, humid climate allows for the cultivation of Piment d'Espelette, harvested in autumn and then dried for at least a fortnight in the open air.

Traditionally, strings of chillies are hung on the facades of houses, forming a strong visual element that marks the village landscape.

This façade drying, beyond its technical function, embodies local know-how and makes the cultivation of chillies immediately recognizable in the Basque built landscape.

La Châtaigne des Cévennes doit its quality to the adaptation of local varieties to the steep slopes and Mediterranean climate. To control erosion and cultivate these tormented terrains, the inhabitants built dry stone walls supporting terraces, called "faïsses" or "bancels". These stepped chestnut groves give the Cévennes slopes their characteristic silhouette and bear witness to an ancestral know-how, still maintained to keep this landscape alive.

Exhibition summary: INAO, 90 years at the service of French agriculture

Download the exhibition panel

Exposition 90 ans INAO - Panneau 10

« COMPRENDRE LE LIEN ENTRE TERROIR, PAYSAGE ET IDENTITÉ DU PRODUIT »